Far out in the Atlantic Ocean lies an unusual patch of calm water, encircled by strong currents, floating roughly 590 miles east of Florida without touching any land. This is the Sargasso Sea, an area long traversed by sailors who often miss the moment they cross into its still, deep-blue waters. For those who linger, the surface becomes dotted with golden-brown Sargassum seaweed, named after the Portuguese word sargaço, referring to grape-like algae. These floating plants drift gently, like tumbleweeds rolling across a watery prairie.

The quiet is surreal no crashing waves or bird cries. Yet the seaweed is teeming with life: rice-sized shrimp, neon-colored baby fish, pale crabs, and newly hatched loggerhead turtles beginning their first ocean journey. The floating mats can grow so thick that early Spanish sailors, including Columbus in 1492, feared their ships might stall forever in the windless expanse.

A Nursery at Sea

Beyond the mystique, the Sargasso Sea serves as a vast 800-mile-wide nursery. Scientists refer to the drifting seaweed clusters as “habitat islands,” where hatchling turtles find protection while their shells harden. Predators like porbeagle sharks patrol the shady depths, and Bermuda storm-petrels dive at the edges to catch shrimp mid-flight.

More than 100 invertebrate species have been found clinging to the Sargassum, living aboard these mobile ecosystems for years until the mats eventually disband.

A Place of Beginnings

Both European and American eels begin life here, appearing as transparent threads that drift with the currents before swimming into faraway rivers—even reaching Indiana. After decades in freshwater, they return across 3,000 miles to spawn and die in the same sea. How they find it remains a mystery. Humpback whales pass through annually, and fast-moving tuna use the area as a thoroughfare to breeding grounds.

An Engine of Climate Stability

Beneath the Sargasso’s placid surface, immense forces are at work. Surface temperatures range from 82–86 °F in summer to 64–68 °F in winter, driving water circulation that moves warm currents north and cool ones south stabilizing Atlantic weather patterns.

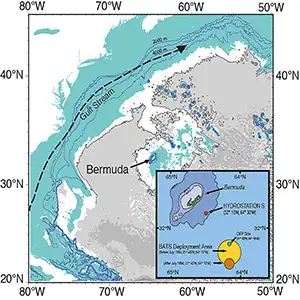

The Sargasso Sea also helps trap carbon dioxide, locking it inside plankton shells that eventually sink to the seabed. Only after years of monitoring did scientists, including Nicholas Bates, realize how much heat the region was absorbing. “The ocean is the warmest it’s been in millions of years,” he warned, noting that such changes could shift rainfall patterns across continents.

Under Threat

Jules Verne once called it “a perfect lake in the open Atlantic,” but today, the Sargasso collects garbage from four converging ocean currents. This slow-moving vortex funnels plastic waste—bags, caps, abandoned fishing gear—into the sea. One study found about 518,000 debris pieces per square mile.

Ship traffic tears through the mats, shedding toxic paint and masking whale communication with noise. Stray nets entangle turtles in what was once their sanctuary.

Decades of Data

Scientists have gathered data from this region near Bermuda since 1954, tracking salinity, temperature, oxygen levels, and pH monthly. Findings show that saltiness increases in winter, while summer rain dilutes the surface. Since the 1980s, the average temperature has risen by about 1°C a small but significant shift. Warmer water layers resist mixing, depriving deeper waters of oxygen and nutrients needed for plankton growth.

New tools like salinity anomaly maps and floating sensors now help track acidification, making the Sargasso Sea one of the best-monitored parts of the ocean.

A Race Against Climate Change

Formed in 2014, the Sargasso Sea Commission calls the area a “biodiversity haven” and advocates for rerouting ships and regulating fishing. Yet with no nation owning the sea, enforcing protections is difficult and expensive.

Meanwhile, Sargassum is growing excessively across the Caribbean, smothering beaches and releasing greenhouse gases as it decomposes—transforming a carbon sink into a carbon source. Ironically, the very organism that gives the sea its identity may not survive in an increasingly acidic ocean.

Why It Matters

If the Sargasso Sea disappears, eels from North America and Europe would lose their birthplace. Humpbacks might arrive to find nothing to eat. Changes in storm patterns and heat absorption could ripple far beyond the Atlantic.

Countries are considering new treaties to curb marine pollution and create marine reserves. Shipping companies are testing quieter engines and biodegradable materials. No single solution will restore the Sargasso Sea, but coordinated efforts could preserve it long enough, perhaps, for the climate to stabilize.

What looks like a blank spot on the map is, in reality, a vital thread linking ecosystems, species, and global weather. The Sargasso Sea may seem silent, but its message is clear: safeguard the calm before the storm arrives.

Be the first to comment